Joseph Smith did not attempt to translate the Kinderhook Plates. When the plates were brought to Nauvoo in 1843, he examined them briefly and compared their characters with material he had from the 1830’s when he translated the Book of Abraham, but he never produced a translation of the forged artifacts now known as the Kinderhook plates.

Later claims that he “translated” the Kinderhook Plates grew from rumor, assumptions by observers, and an editorial mistake in an early Church history that presented a secretary’s journal entry in the first person as if it were Joseph Smith speaking. When the original documents are compared, the supposed Kinderhook Plates “translation” traces back to older notebook material of Joseph Smith, not to the plates.

Doctrine of Revelation Explained

Latter-day Saints believe that true prophetic translation happens only when God authorizes it. Joseph Smith did not claim the power to translate every unknown artifact that came into his hands, and he did not treat curiosity or public pressure as a reason to declare something ancient scripture.

The “kinderhook plates” story is often told as if Joseph Smith tried to translate a fake record and failed. The historical evidence points in a different direction: he did not attempt a translation of the Kinderhook Plates, and the later “translation” claim comes from assumptions and misunderstandings about what he was actually doing in the moment.

How the Kinderhook Plates Are Used as an Accusation

Anti-Mormons frequently cite a supposed Kinderhook Plates translation to argue that Joseph Smith was not a prophet and therefore that The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was founded by a fraud. The claim usually depends on one idea: that Joseph Smith looked at the plates, produced a translation, and was proven wrong because the plates were later exposed as a hoax.

The problem is that the key premise is mistaken. Joseph Smith did not attempt to translate the Kinderhook Plates.

The Strange Origin of the Kinderhook Plates in 1843

In 1843, six small, engraved metal plates were reported as “discovered” near Kinderhook, Illinois, and were soon brought to Nauvoo for examination. Unknown at the time, the plates were part of a deliberate hoax. The episode unfolded in a period when both believers and skeptics were fascinated by the possibility of ancient records, especially as public debates about the Book of Mormon continued.

News of the find spread quickly. The plates were briefly displayed in nearby towns, drawing local attention and curiosity. Two members of the Church were present at the excavation, which added credibility in the eyes of many Saints. As a result, many, including Parley P. Pratt, assumed the plates were genuine and hoped they might represent another ancient record similar to those already described in scripture. That excitement naturally led to speculation, even though no official claim had been made about their origin or meaning.

When the plates were brought to Nauvoo, Joseph Smith examined them briefly. He compared the characters on the plates with copied characters from earlier study projects. This examination was limited and informal. There was no attempt to purchase the plates, no effort to retain them, no scribes were assigned, and no translation was produced or published. After a short time, the plates were returned to their owners in Pike County.

Once returned, the plates quickly faded from attention. They were not referenced again in Church publications as a source of doctrine or revelation, and no effort was made to follow up on them. Whatever initial curiosity existed was short lived. Over time, the plates were lost, discarded, or otherwise forgotten, and the episode passed into obscurity.

A Key Statement from the Hoaxers – “Joseph Would Not Attempt to Translate”

William Fugate, one of the men involved in the attempted fraud explained that Joseph Smith was not willing to translate the Kinderhook Plates and would not do so without outside confirmation. He said,

“Joseph would not [have] attempted to translate the plates without them being certified from Paris and London.”

This directly contradicts the accusation that Joseph Smith made a prophetic translation of the Kinderhook Plates by the very men who were trying to make Joseph attempt to translate them and look foolish. The outside confirmation was impossible because the fraudsters knew that the plates were not authentic and that the characters were made up.

What Joseph Smith Actually Did in Nauvoo

According to a non member eye witness who was there when Joseph handled the plates, and later wrote a letter to the New York Herald about it, when Joseph examined the Kinderhook Plates he compared their characters with material he from his “Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language” project.

This man believed that Joseph Smith could have translated the plates. This comparison of characters from an unknown source is one of the main reasons people assumed a Kinderhook Plates translation happened. Observers saw Joseph Smith consult a notebook and inferred that a translation was underway.

Did Joseph Smith Say, “I Translated The Plates”

Another major source of confusion comes from a line that appeared in an early published Church history written in the first person, as if Joseph Smith himself were speaking. This wording appears in the 1909 first edition of the History of the Church and includes language such as:

“I translated…”

For many years, readers reasonably assumed this meant that Joseph Smith personally declared he had translated the Kinderhook plates.

Later analysis showed that this wording did not originate with Joseph Smith at all. Instead, it came from a brief, third-person entry in William Clayton’s personal journal. When historians later compiled Joseph Smith’s history, it was common practice at the time to rewrite third-person source material into a first-person narrative voice. In this case, that editorial process transformed Clayton’s summary into what appeared to be a direct statement from Joseph.

This change in narrative voice is a major reason the idea of a Kinderhook Plates “translation” persisted for so long, even though no such translation was ever recorded, dictated, witnessed, or published.

William Clayton was one of Joseph Smith’s clerks, but we do not know what information Clayton was working from when he wrote his journal entry. There is no evidence that he witnessed a translation, that Joseph claimed revelation, or even that Clayton was present when Joseph examined the plates. What Clayton recorded appears to be an assumption on a document he saw that he concluded was the Kinderhook plates document.

The 1835 Grammar and Egyptian Alphabet Project

The notebook Joseph Smith consulted while comparing characters when examining the Kinderhook Plates was related to a 1835 project commonly called the “Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language,” often grouped with documents known as the Kirtland Egyptian Papers. Whatever a reader concludes about that project, it is not best understood as Joseph Smith’s standard method of prophetic translation. It reflects an experimental attempt to organize symbols and ideas, including symbolic meanings tied to spiritual concepts.

The Grammar Page That Matches Clayton’s Description

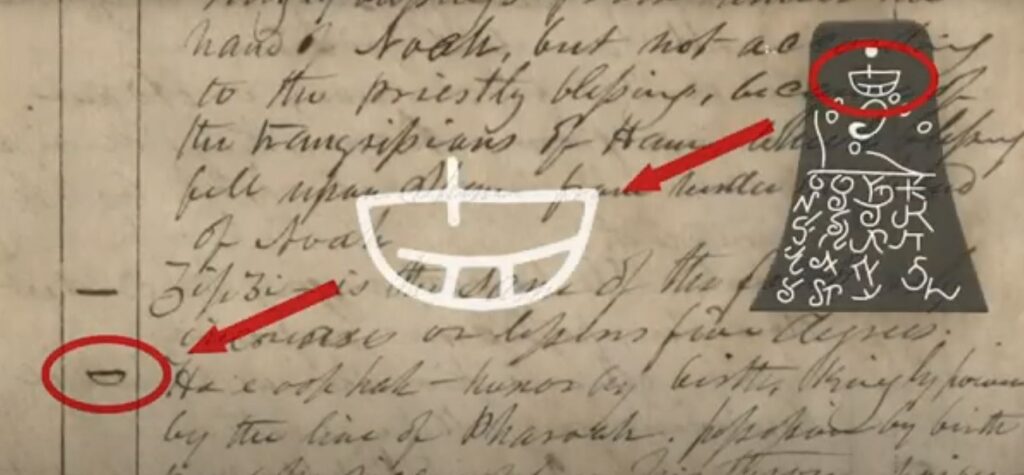

One page of the Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language contains a character that resembles a boat. The Kinderhook plates also include a prominent symbol with a similar boat-like shape. When Joseph Smith examined the plates, eyewitnesses report that this Egyptian notebook was physically present and being consulted while characters were compared.

The relevant page in the Joseph Smith Papers is here.

William Clayton later recorded the following entry in his journal:

“President J. has translated a portion and says they contain the history of the person with whom they were found, and he was a descendant of Ham through the loins of Pharaoh king of Egypt, and that he received his kingdom from the ruler of heaven and earth.”

On the GAEL page containing the boat-like character, the accompanying text includes language describing royal lineage through Pharaoh, descent connected to Ham, kingly authority by birth, and dominion granted by heaven and earth. The overlap in wording and themes is direct and specific.

Clayton was not involved in the 1835 Egyptian project and would not have known that this notebook material predated the Kinderhook plates by several years. It appears that Clayton assumed that what he saw on that page represented Joseph’s translation of the Kinderhook plates, when in fact it was older material being referenced during a comparison of characters.

This is the crucial evidentiary point. When Clayton’s journal entry is placed alongside the GAEL text, the correspondence strongly indicates that the notebook page was the source of the translation-like language. The language did not come from the Kinderhook plates themselves, nor from a revealed translation, but from Clayton’s misunderstanding of existing Egyptian notes being consulted at the time.

Timeline of the Kinderhook Plates

1835

W. W. Phelps, Oliver Cowdery, Willard Richards, and Joseph Smith work on a “pure language” or symbolic study project that attempts to assign layered meanings, degrees, and concepts to characters. This effort draws on ideas connected to sacred language and incorporates characters, some of which were copied from the Egyptian papyri associated with the newly translated Book of Abraham. It also reflects themes and language tied to earlier revelations, including Doctrine and Covenants sections 76, 84, and 88, which emphasize graded glory, priesthood order, and sacred knowledge. The notes from this effort are preserved in a notebook titled the Grammar and Alphabet of the Egyptian Language (GAEL). The project is exploratory and is later abandoned.

April 23, 1843

Six engraved, bell-shaped metal plates are “discovered” in a burial mound near Kinderhook, Illinois. The discovery is later revealed to be an elaborate hoax. The men responsible stage a public excavation, deliberately planting the plates in advance and arranging for witnesses to be present. Among those present at the dig are two members of the Church, lending credibility to the discovery in the eyes of local residents and Latter-day Saints. Human bones are also uncovered at the site, reinforcing the appearance of an ancient burial.

Late April 1843

Joseph Smith briefly examines the Kinderhook plates and compares their characters with his Hebrew Lexicon and his Egyptian character notes. He declines to attempt any translation unless the plates are first authenticated by recognized antiquarian societies in Europe, specifically mentioning Paris and England. According to Wilbur Fugate, one of the men who later admitted to creating the hoax, Joseph “would not attempt to translate them.” The plates are returned to their owners and quickly fall out of relevance.

May 1, 1843

William Clayton records a brief entry in his personal journal stating that “President J. has translated a portion” of the Kinderhook plates. Clayton appears to assume that material he observed in Joseph Smith’s possession, specifically the earlier GAEL notebook, represented a translation of the Kinderhook plates. Clayton was not involved in the 1835 Egyptian project and lacked context for that notebook, which led to a misunderstanding that later became central to the controversy.

May, 1843

Excitement spreads among Church members after reports circulate about the discovery of the Kinderhook plates. Many Saints assume the plates may be authentic and view them as potential additional evidence of ancient metal records in North America, which they believe would further support the Book of Mormon. This enthusiasm is driven by speculation and newspaper reporting rather than any official claim from Joseph Smith.

June 27, 1844

Joseph Smith is murdered in Carthage, Illinois.

1879

James T. Cobb, an ex–Latter-day Saint and outspoken critic of the Church, contacts Wilbur Fugate seeking information about the Kinderhook plates in an effort to damage the Church. This inquiry prompts Fugate to respond. In his letter, Fugate confesses that the plates were a hoax, explains how they were manufactured, and confirms that Joseph Smith refused to translate them without outside authentication.

1909

The History of the Church was published in 1909 under the direction of B. H. Roberts using journals and papers from Joseph Smith and his associates, including William Clayton. Following common historical practice at the time, editors rewrote third-person source material into a first-person narrative as if Joseph himself were speaking. In doing so, Clayton’s brief journal comment about the Kinderhook plates was converted into a first-person statement, making it appear that Joseph said “I have translated.” This editorial choice, not any contemporary statement by Joseph Smith, is the main reason later readers believed he claimed to have translated the Kinderhook plates.

1981

Scientific testing of a surviving Kinderhook plate confirms it was produced using 19th-century acid-etching techniques. The Church publishes the results, formally closing the question of the plates’ authenticity. This publication also brings an end to lingering rumors held by some Saints for decades that the Kinderhook plates represented another ancient North American record.

How the Translation Assumption Became “Fact”

People in Nauvoo were already speculating that the Kinderhook plates were authentic. As the story spread, it was repeated with growing confidence, and over time the details were simplified into a single claim: “Joseph Smith translated them.”

That process affected both members and non-members. As the story circulated, layers of assumption replaced careful observation. What began as curiosity and comparison gradually took on the appearance of a settled historical conclusion, even though no translation was ever produced.

For years, even some Latter-day Saint scholars accepted the idea that Joseph Smith had attempted a secular, non-inspired translation of the Kinderhook plates. Apologetic explanations were written to account for that assumption, often suggesting that Joseph was experimenting with language rather than claiming revelation. Those explanations rested on a faulty premise: that William Clayton’s journal reflected an actual translation attempt, when it more likely reflected Clayton misunderstanding the record Joseph consulted.

Why the “Secular Translation” Defense Persisted

For a long time, defenders assumed they needed to explain why Joseph Smith translated the Kinderhook plates at all. That assumption gave rise to the idea of a purely secular translation attempt. What was missing was a serious examination of the connection between Clayton’s journal entry and the pre-existing 1835 Grammar and Egyptian Alphabet material.

Once that connection is recognized, the need for a “secular translation” defense largely disappears. The evidence fits a simpler explanation. Joseph Smith compared characters and consulted existing notes. Clayton assumed those notes represented a translation of the Kinderhook plates. Later editors unintentionally reinforced the confusion by rewriting Clayton’s third-person summary into Joseph’s first-person voice.

Clarifying Common Misunderstandings

This belief is sometimes misunderstood as proof that Joseph Smith attempted to translate a fraudulent artifact and failed. The documentary record does not support that conclusion. The strongest evidence for a Kinderhook Plates “translation” traces back to assumptions about what Joseph Smith was consulting, combined with later editorial choices that made an observer’s journal entry read as if Joseph Smith were speaking in the first person.

Latter-day Saints do not believe Joseph Smith produced a revealed translation of the Kinderhook Plates, and the most careful reading of the sources indicates that he did not attempt one.

Faithful Affirmation

The Kinderhook Plates episode shows how quickly rumor and misattribution can reshape a historical story. When the original documents are compared carefully, the claim that Joseph Smith translated the Kinderhook Plates does not hold.